Socialist Holiday Dreams and Realities in the GDR

Holidays in your own country: What was an annoying restriction during the pandemic years and is now touted as a climate-friendly alternative, was normality for the majority of the GDR population. Although their travel destinations were limited, working people had the right to holidays.

In her article, architectural historian and monument conservator Daniela Spiegel outlines how this was coordinated through the targeted infrastructural development and expansion of recreational areas. She also explores how, on the one hand, the concept of holidays changed and, on the other, the holiday architecture of the GDR developed typologically and conceptually.

“Visafrei bis nach Hawaii” (“Visa-free to Hawaii”) was one of the central slogans chanted by GDR citizens during the demonstrations in the autumn of 1989. The desire behind this demand was not to leave the country forever, but to be able to choose their vacation destinations freely. Because for the GDR inhabitants, holidays were not usually about satisfying their desire to travel and getting to know other countries, quite the contrary. Due to the rigid travel restrictions, which strictly regulated travel abroad and only allowed trips to selected socialist brother states, three quarters of the population spent most of their holidays in their own country.

Despite, or perhaps because of the restricted freedom to travel, the “recreation system” played a central role in the GDR. The right to holidays for working people was a fundamental and, from the outset, constitutionally enshrined component of the socialist state, which was far ahead of West Germany in this respect. The state considered holidays as a governmental duty and used them for its own legitimisation and representation, to demonstrate the superiority of socialism and the state’s welfare work both internally and externally. The main provider of the state recreation system was the Holiday Service of the Free German Trade Union Federation (Freier Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, FDGB), founded in 1947, but companies and combines also provided large numbers of holiday places for their workers. All trade union and company trips were subsidised by the state by up to two thirds.

A corresponding infrastructure was needed to make holiday trips possible: from the Baltic coast to Lusatia, from Lake Müritz to the Thuringian Forest, countless holiday facilities were built. As in all of Europe, modern mass tourism in the GDR also brought about a massive transformation of the landscape. Accordingly, the architectural relics of this boom period are viewed today more from the perspective of landscape destruction than in terms of their architectural quality. However, the holiday architecture of the GDR was much more than the “Platte” – the industrialised building – on the beach or in the mountains. It represented an attractive playing field for planners and architects, offering scope for individual designs within the tightly-strung corset of the planned economy.(1)

1950s – The beginning

The initial property stock of the FDGB Holiday Service consisted of a few union-owned old buildings and a manageable number of expropriated castles and manor houses, which – instrumentalised for propaganda purposes – were portrayed as rightful acquisitions by the formerly oppressed working class.(2) With further expropriations in the early 1950s, several guesthouses and hotels were added. At the same time, the FDGB also began constructing a handful of new buildings in traditional tourist regions. These were referred to as “Ferienheime” (holiday homes), in keeping with the tradition of the labour movement, emphasising the collective aspect of holidays spent together.

In the early years, the propagandistic interpretation of holidays as a privilege previously reserved for the upper class, now made accessible to the entire population, was extremely important. Ensuring and enforcing statutory holiday entitlements for the regeneration of the workforce was a fundamental aspect of the young republic’s self-image. This corresponded to an ideological interpretation that clearly set itself apart from the Western perspective – holidays and leisure time were seen as complements to the working world and by no means as escapes from it. Consequently, the focus was initially on the regenerative aspects of holidays, aimed at maintaining the workforce’s productivity. This led architects to draw more inspiration from sanatorium architecture than hotel architecture when designing new buildings. Typical features included gently curved, south-facing accomodation with cantilevered balconies. The first buildings were very heterogeneous in design, showcasing all the parallel evolving styles of the time: from socialist classicism to “national traditions” and influences of classical modernism. Tendencies of the “Heimat-Style” from the 1930s also repeatedly appeared. This can be explained both by the continuity in the careers of the architects and by the regional-traditional references being seen as an appropriate architectural vocabulary for these projects that are closely tied to the respective regional culture and nature.

1960s – Attempts at standardisation

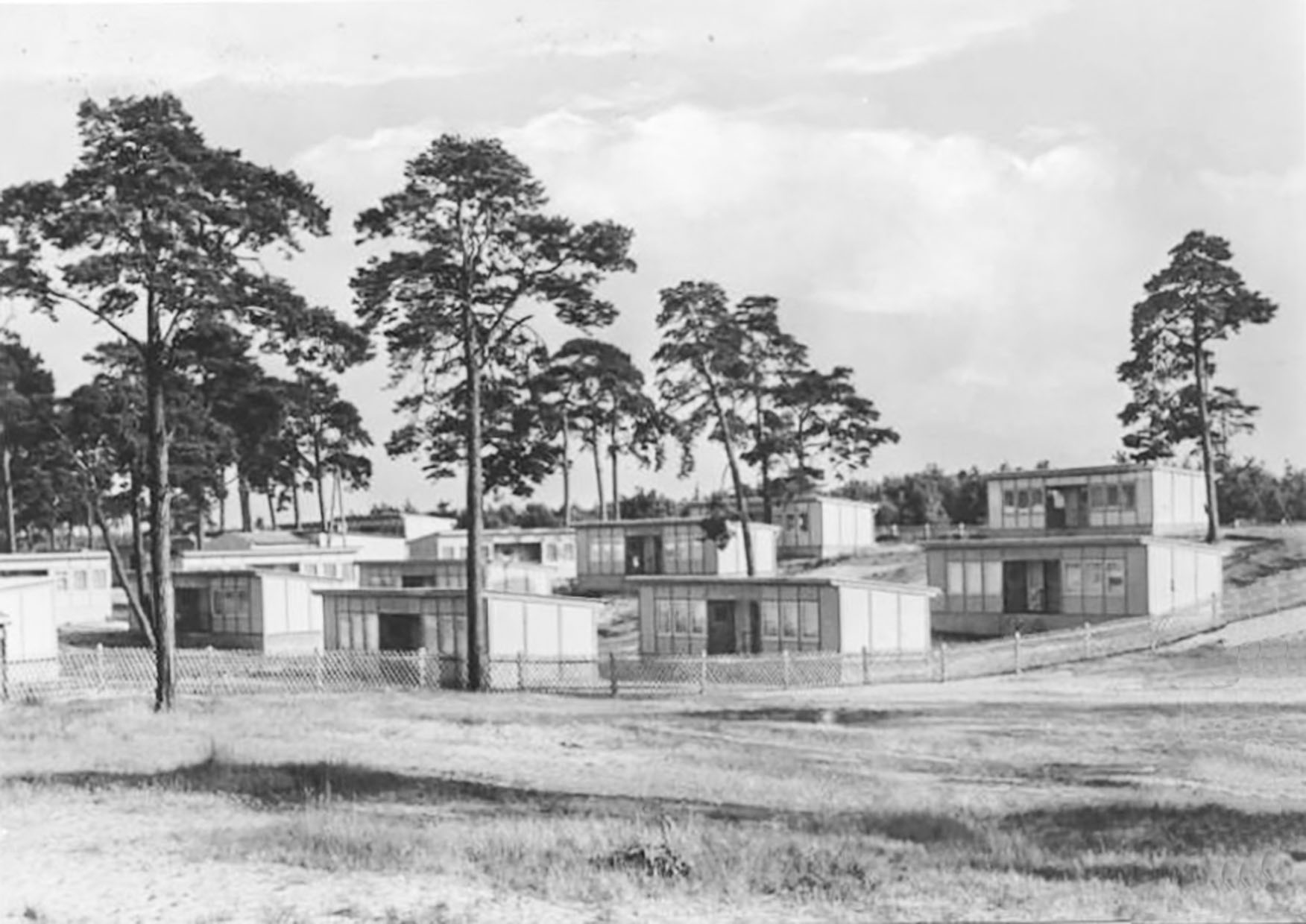

As the number of union members grew steadily, so did the number of people entitled to holidays. It soon became clear that the traditional holiday regions of the Baltic Sea, Harz Mountains, Thuringian Forest and Erz Mountains would not suffice and that quick structural solutions were needed to meet the enormous demand. While searching for new recreational areas, the potential of the Mecklenburg Lake District was recognised, which had previously been largely untapped for tourism.(3) The FDGB holiday resort Völkerfreundschaft opened in Klink an der Müritz as early as 1962. This was a complex resort consisting of a community centre for catering and social facilities as well as a large number of individual bungalows arranged in curved rows on a spacious lakeside area.

Both economically and conceptually, the bungalow resorts opened up new possibilities. Firstly, the bungalows offered a more informal and more nature-oriented form of recreation, especially for families for whom there was not enough space in the holiday homes. Secondly, the bungalows, designed with prefabricated elements in lightweight construction, were inexpensive and quick and easy to erect. A number of different types were created, which were also used in allotment gardens and weekend resorts. Of course, these also included the A-frame cabins (“Finnhütten”), which are now considered typical of the GDR, although they can be found all over the world. Holiday villages became increasingly popular for company holidays, whereas the FDGB soon returned to focusing on the construction holiday hostels. Thereby, the union followed the guidelines of the state leadership, which rejected bungalow estates as too small-scale a solution and instead demanded “the construction of multi-storey type buildings using rational construction methods (…) for the recreation of working people”(4), as was already common practice in housing construction.

With the onset of attempts at standardisation, the lodging house was separated from the communal area and the spacious balconies disappeared. Henceforth, holiday hostels typically consisted of a narrow, multi-storey lodging section with a low-rise building, either adjoining or sometimes even pushed underneath, at the side or extending around the corner, which accommodated the communal and service areas. Solutions from residential construction were often adapted for the lodging sections. One example of this is the holiday hostel Herbert Warnke, generated from a type project of the Halle Housing Construction Combine (WBK Halle), which was built between 1969 and 1971 as an extension to the Klink holiday resort.(5) An elegant and dynamic-looking building that proved to be absolutely state-of-the-art with its Y-shaped floor plan, elevated on pilotis, delicate flying roof and staggered façade elements.

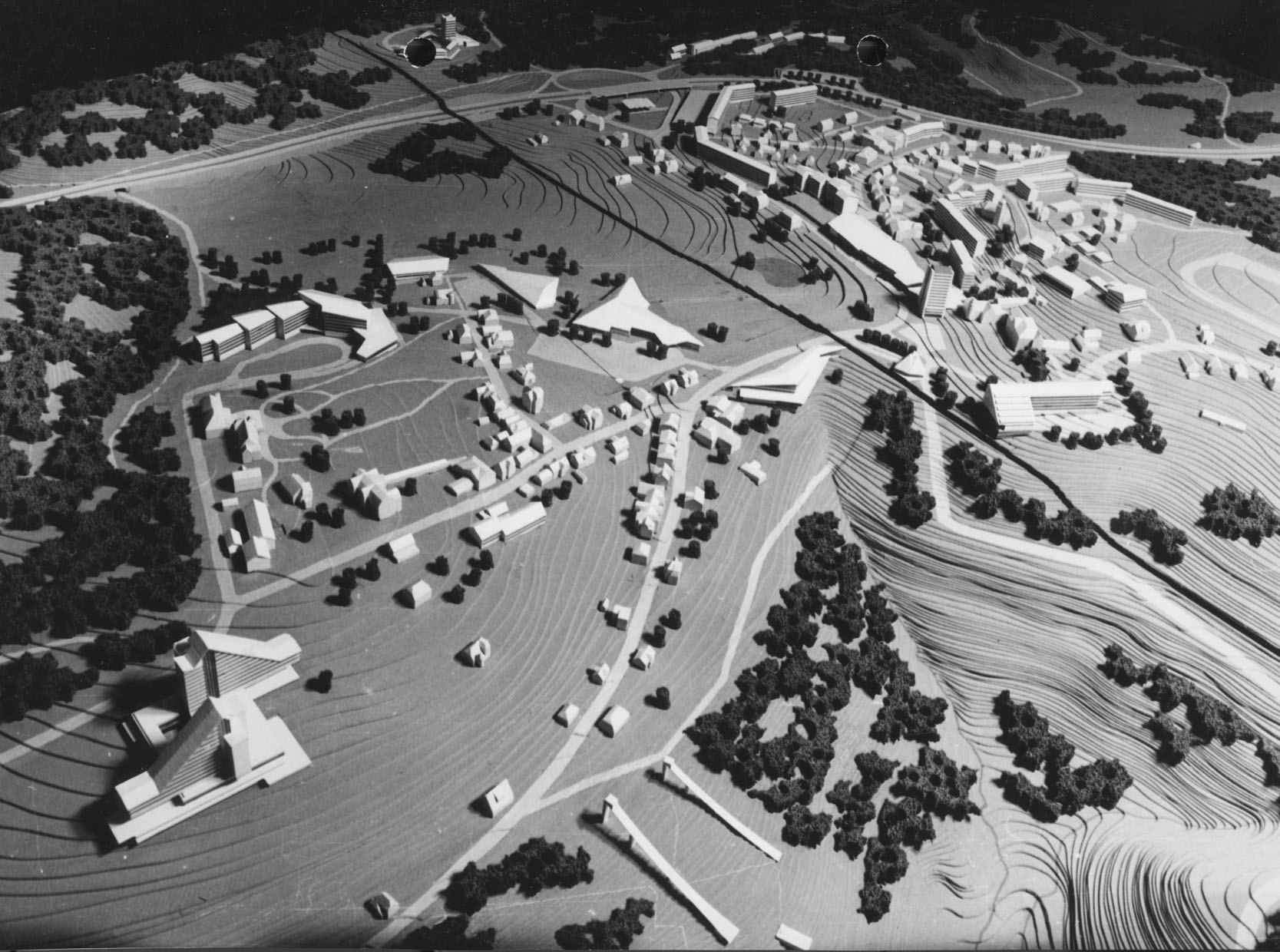

Despite all efforts to establish inland waters for tourism, the rush to the traditional holiday regions, especially the Baltic coast, remained unabated. To counteract this, on the orders of Walter Ulbricht, ambitious plans to create a huge tourist centre on the island of Rügen were initiated in the late 1960s, when the major urban development projects of socialist city centre designs were also underway.(6) On the so-called Schaabe, a narrow spit in the north of the island, the “First Socialist Seaside Resort of the GDR” was to be built, with a final capacity of 20,000 beds. A figure that had once been targeted for a major tourism project on Rügen, although the obvious comparison to the National Socialist “Resort of the Twenty Thousand” in Prora was of course never drawn. The surviving designs show urban planning similarities with contemporaneous tourism projects on the Black Sea coast: typified hotel towers alternating with up to five-storey accommodation blocks and low-rise communal buildings, along with extensive leisure facilities – including tennis courts, seawater wave pools, bowling alleys, dance halls and a theatre/cultural centre. The ambitious project was not implemented, as the ongoing economic problems of the FDGB, lack of financing and construction capacities caused the planning to essentially dissipate in the Baltic sand.

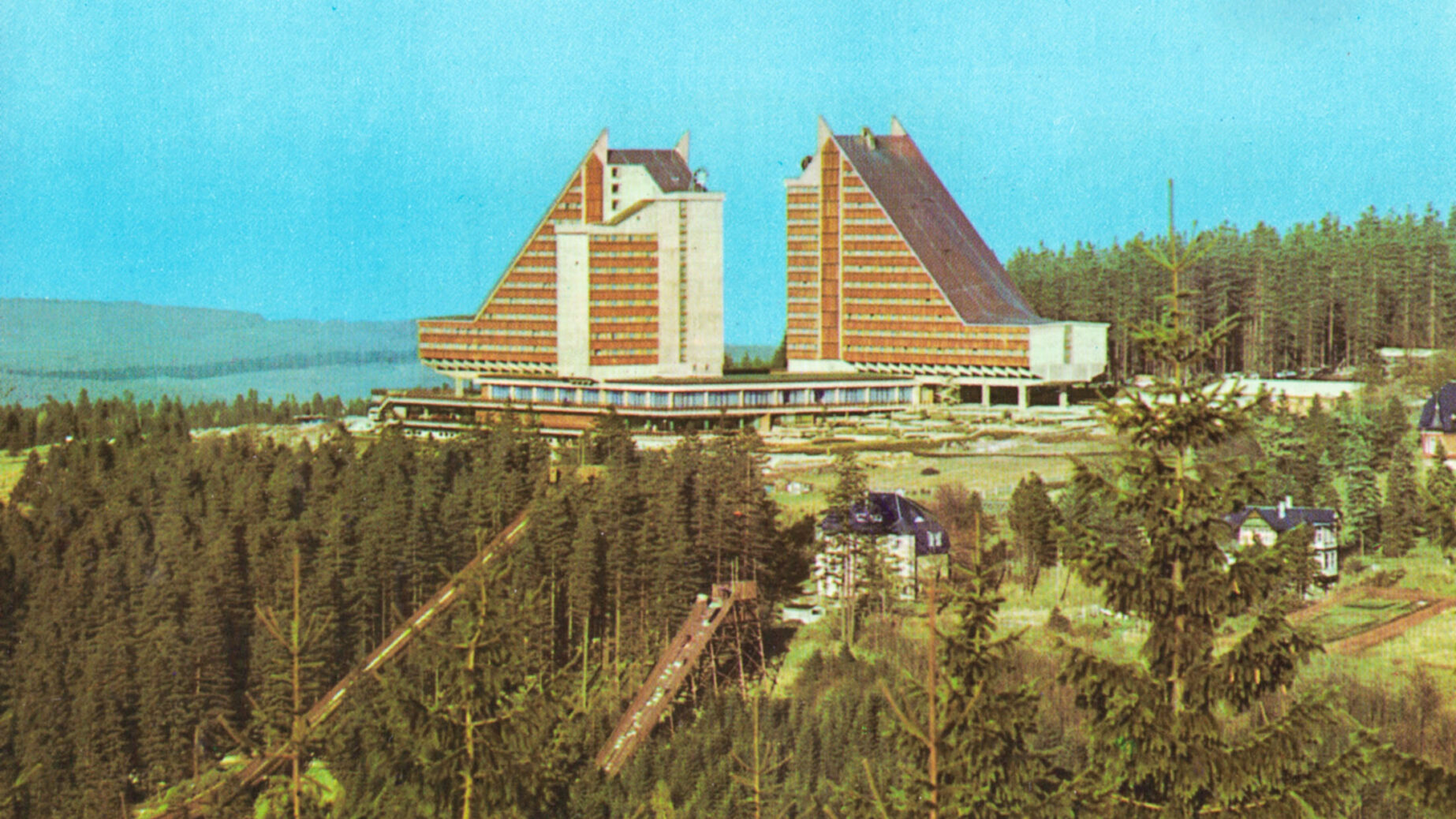

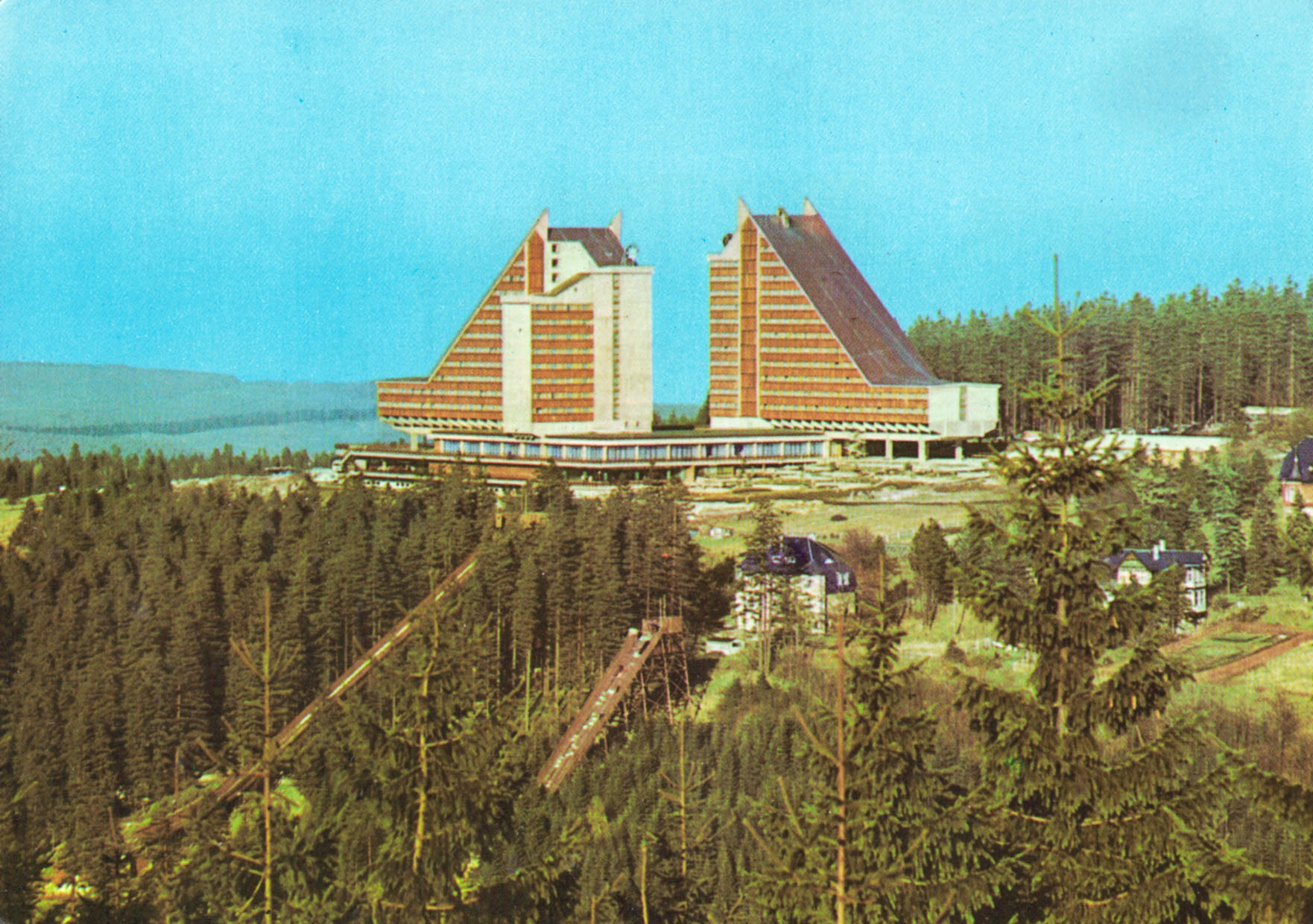

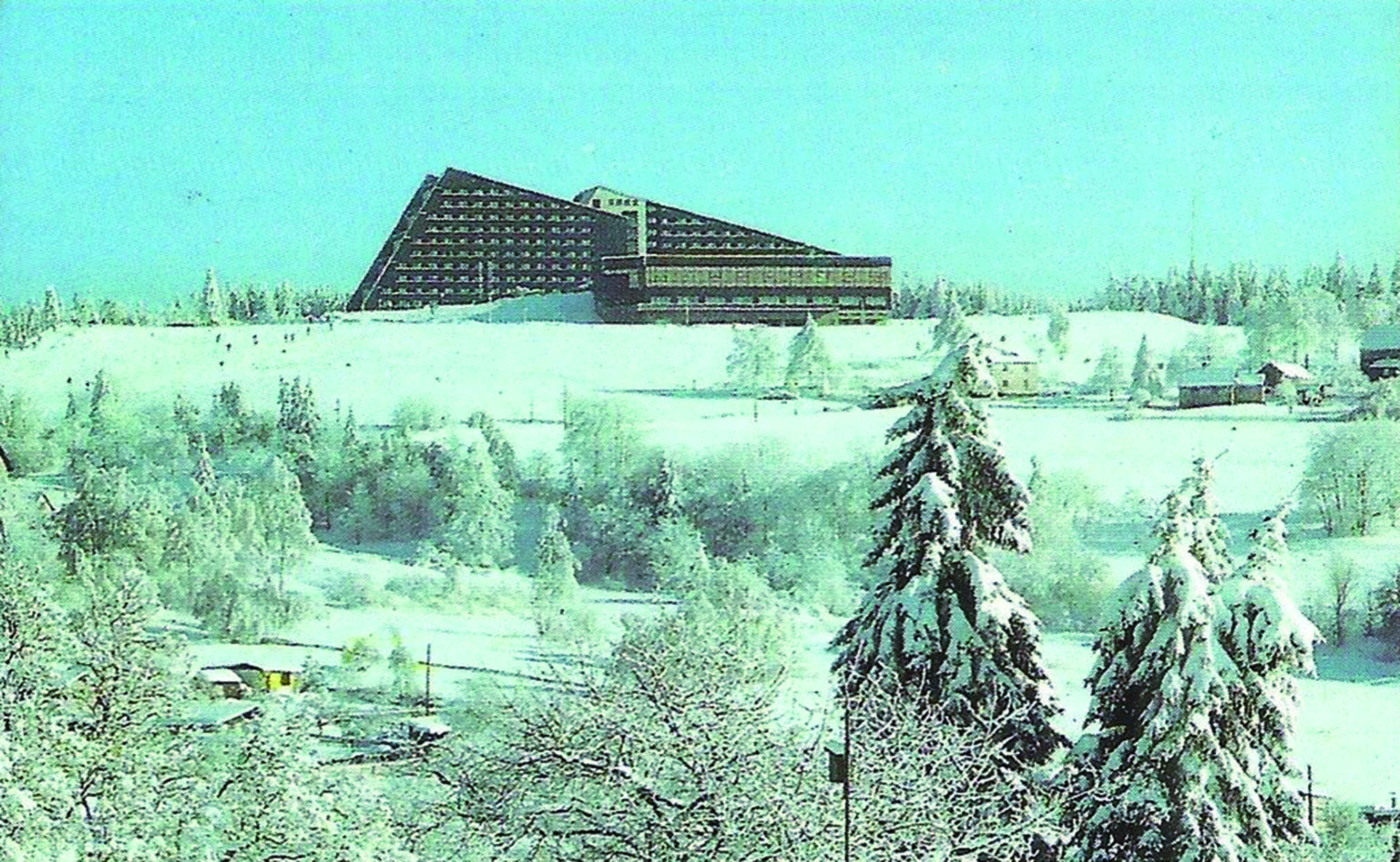

Another major project, however, the expansion of Oberhof, a health resort in the Thuringian Forest, into an international winter sports and recreation centre, was at least partially executed. It also falls within the context of visionary socialist city centre designs of the late 1960s under Ulbricht’s personal aegis. With Oberhof, he aimed to transform his personal favourite holiday destination “into a magnet for international tourism” that met the highest standards.(7) To guarantee this, the responsible district office for urban planning in Suhl was supported by the experimental workshop of the Deutsche Bauakademie, headed by Hermann Henselmann, which had also been involved in the Schaabe project. In a “socialist joint effort”, they developed a “complex reconstruction” of the site, as urban redevelopment schemes were referred to in the language of the time. The plan envisioned a sequence of low, crystalline-shaped, large-roof buildings with interspersed dominant high-rises. The design was conceived as a holistic sculpture – it was intended to become the second landscape, highly modern in form yet regionally and culturally embedded in the Thuringian cultural landscape through the use of local materials such as slate, natural stone and wooden shingles. The planning commenced with the previously planned Panorama Hotel (1967-69) at the north end of the town. It was the first new construction of the state-owned INTERHOTEL association, founded just two years prior, intended to meet the needs of foreign guests with large amounts of foreign currency, which they hoped to attract in the future. Accordingly, besides comfortable amenities, spectacular architecture was also desired. The commissioned Yugoslavian collective designed the striking image of two raised triangular buildings accommodating the hotel rooms with a low-rise structure underneath for gastronomy, leisure facilities and administration, which were interpreted both as mountain peak motifs and ski jumps. The building was celebrated as “the first landscape-oriented Interhotel of the GDR”.

The second realised building was the FDGB holiday hostel Rennsteig, prominently positioned in the city centre. Also an emblematic structure, its conically tapering high-rise section with the monumental “R” on the gable invoked the shape of the historical boundary stones of the eponymous historic hiking trail. Typologically, both buildings thus fit into the context of Architecture parlante, as their architecture referenced the tourist identity symbols of the location – winter sports and hiking. Symbolic architecture was an international trend at that time, and the mountain peak motif in particular was a popular design for alpine hotels.

1970s – Comprehensive development

The complex transformation of Oberhof was only partially realised – like many visionary construction projects, it fell victim to the political and economic redirection that accompanied the transition of power from Walter Ulbricht to Erich Honecker in June 1971. Unlike Ulbricht, who declared socialism as a goal to be achieved in the future, the new party leader propagated socialism as “really existing”. Consequently, quick successes had to be achieved to demonstrate the improved living conditions of the population. Although the main focus was on housing construction, a comprehensive new construction programme was also initiated in the recreation sector. Instead of complicated and costly individual projects, the focus was now on rapid, comprehensive development. Between 1971 and 1980, about 40 new holiday homes with a total capacity of approximately 12,900 beds were built, and another 16 buildings with over 9,000 beds were added in the last decade of the GDR’s existence. These were usually quick-to-build type projects with narrow, multi-storey lodging blocks, often directly taken from standardized housing construction.They were built in decentralised locations in existing vacation areas, which they strongly influenced due to their sheer size. Such buildings were constructed in almost every existing seaside resort on the Baltic coast, always in immediate vicinity of to the beach, but usually on the outskirts, so that the townscapes of the seaside resorts remained largely intact. Only the traditional seaside resort of Binz on the island of Rügen underwent large-scale expansion in the 1970s. On behalf of the FDGB Holiday Service, the Rostock Housing Construction Combine (WBK Rostock) built numerous large complexes there in several construction phases, not attempting to conceal their typological origin from residential construction. The noticeable lack of willingness to adapt the recreational buildings to the existing townscapes is surprising, considering that the architects of the northern districts were actually leading the way in the development of neighbourhood-compatible design solutions for industrial housing construction.

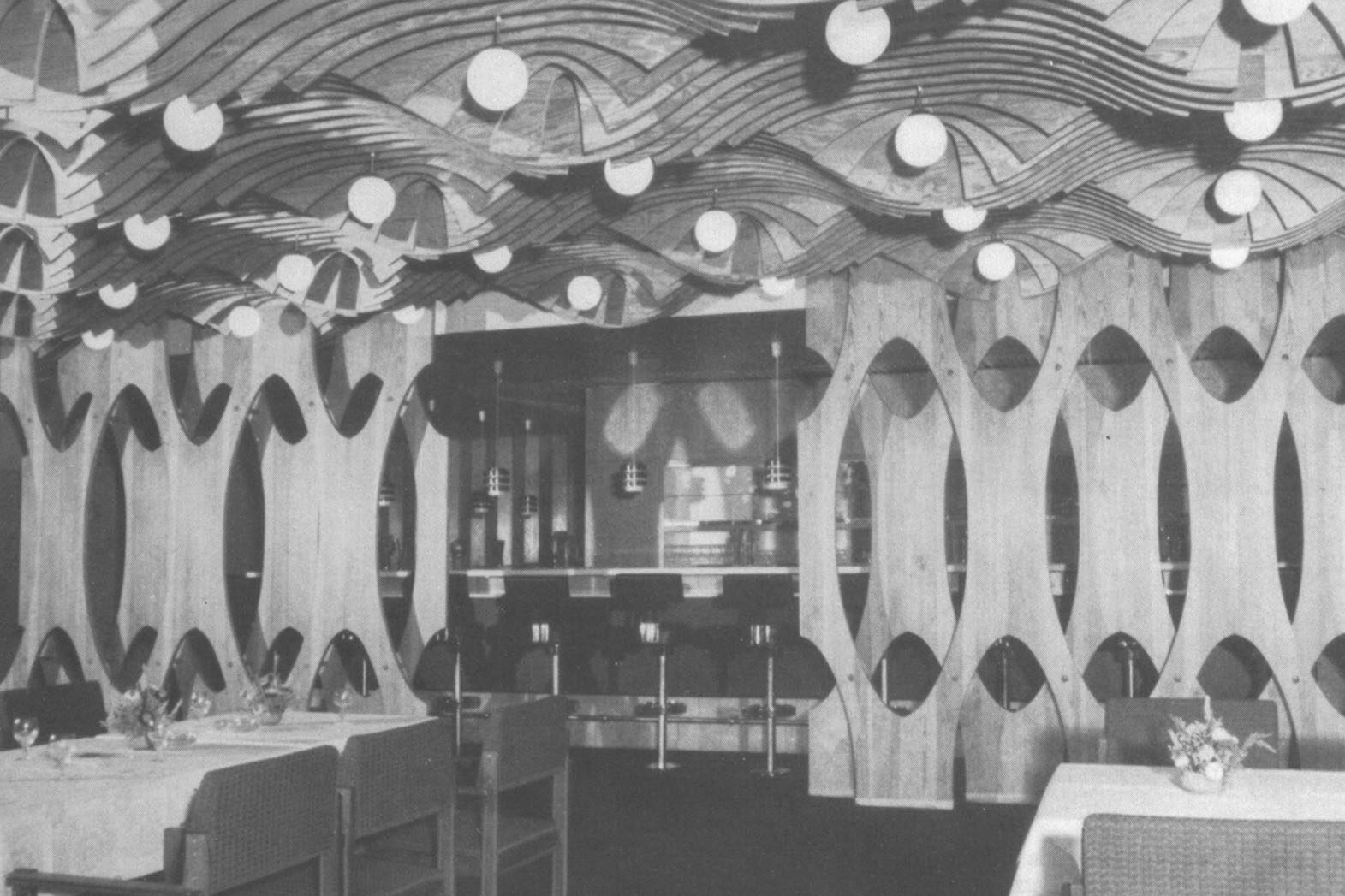

In the low mountain regions, favoured by the varied topography, exposed locations were often chosen, and their urban effect was further emphasised by prominent building forms. Despite the architectural dominance, some projects also demonstrated the designers’ intention to integrate the holiday hostels into the landscape through their design. A frequently chosen motif was the continuation of the mountain topography, already begun in Oberhof, through stepped or slanted structures and the use of local materials (natural stone, slate, wood). Both the materials and the roof design also accommodated the challenging weather conditions. Integration into the local culture and nature was also an important theme in the interior design of the holiday facilities. In contrast to the rather limited scope for design in the architecture, greater possibilities for expression were available here, which the commissioned interior designers and artists used in a highly creative manner. They did their best to use artistically designed rooms to make holiday guests forget, at least inside, that the basic structure of the building was often the same as that of the residential buildings in which they lived.

Artistic design elements such as murals or room dividers were commissioned for the communal rooms, which addressed general themes like the seasons, natural elements and holidays, often referencing the respective local culture to create a “regionally typical character”(8).

The most interesting furnishings, however, were to be found in the small gastronomic themed taverns in the basement, which literally rooted the holiday hostels in local tradition. Here, the need for authenticity and local colour was satisfied, which the holidaymakers could hardly live out in the forced mass catering. Nevertheless, interior designers and artists tried to interpret the respective traditions in a contemporary way. For example, in the FDGB hostel Am Fichtelberg in Oberwiesenthal in the Ore Mountains, there was a modern interpretation of a silver mine tunnel. For the Knappenstube (pitman’s parlour) with its adjoining Steigerzimmer (miners’ room), the renowned metal artist Clauss Dietel created an impressive ceiling sculpture consisting of closely spaced galvanised rainwater pipes into which individual light fittings were integrated, lending the otherwise unlit room with its deep black slate floor a mysterious atmosphere. Such small themed rooms became part of the basic equipment of every FDGB holiday home from the mid-1970s onwards and reflected the increasing differentiation of leisure activities on offer. Equipped with swimming pools, mini golf courses, themed restaurants, nightclubs and other facilities designed to satisfy the holiday dreams of the population, the holiday hostels’ conceptual design increasingly resembled hotels. However, as much as the FDGB Holiday Service endeavoured to create the most appealing architectural framework possible for the holidays of its trade union members, the “socialist holiday dreams” ultimately remained unfulfilled for GDR citizens. The longing for different worlds and a temporary escape from everyday life – an intrinsic part of the idea of travelling – was not satisfied. The growing disappointment with this situation became increasingly powerful over the last decade of the GDR and ultimately contributed to the downfall of the state.

This article first appeared in issue no. 3 2024 of Die Architekt, the magazine of the Association of German Architects BDA.

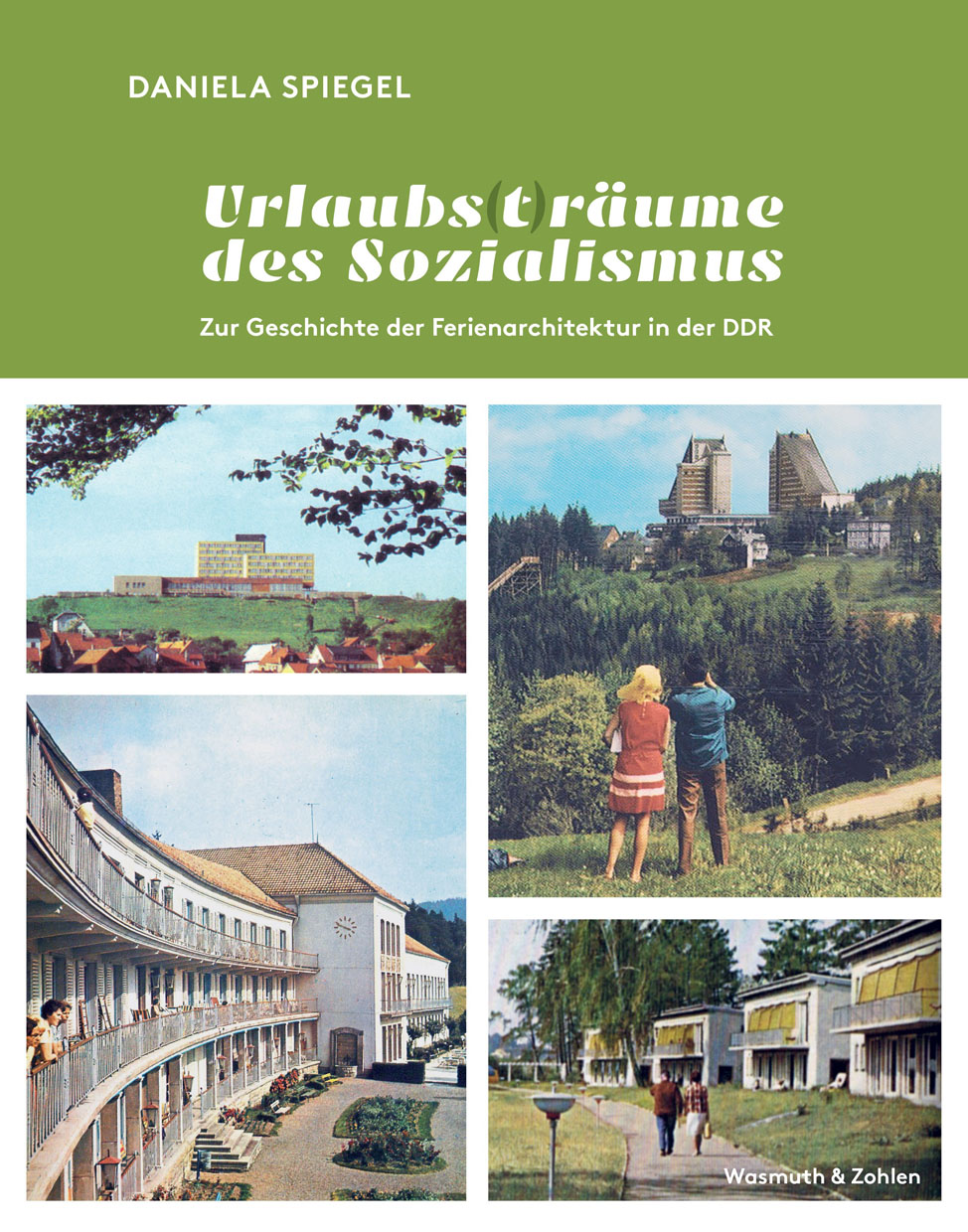

The article is based on the habilitation thesis Urlaubs(t)räume des Sozialismus. On the history of vacation architecture in the GDR in a European context by Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Daniela Spiegel, that was published by Wasmuth & Zohlen Verlag in 2020.

About the author

Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Daniela Spiegel has been a professor of Heritage Conservation and Architectural History at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar and a member of the DFG Research Training Group “Identity and Heritage” since April 2023. Previously, she taught Architectural History and Heritage Conservation at Anhalt University of Applied Sciences. Her research focusses on heritage conservation theories and the architectural and urban planning history of the 20th century. In addition to the architecture and urban planning of Italian fascism, she explores the architectural, especially the tourist heritage of the GDR. This article summarises the results of a long-term research project in which the author examined how the architectural framework for state-controlled holiday experience in the GDR was designed and what concepts, ideas and influences from Eastern and Western Europe influenced GDR holiday architecture.

Footnotes

1 – Spiegel, Daniela: Urlaubs(t)räume des Sozialismus. Zur Geschichte der Ferienarchitektur in der DDR, Berlin 2020.

2 – On the history of the FDGB Holiday Service, cf.: Görlich, Christopher: Urlaub vom Staat. Tourismus in der DDR, Zeithistorische Studien 50, Cologne 2012.

3 – The identification of the Mecklenburg Lake District as a future recreational area was one of the key findings of a study carried out by landscape architect Frank Erich Carl on behalf of the Deutsche Bauakademie. Carl, Frank Erich: Erholungswesen und Landschaft. Ein Beitrag zur Planung der Ferienerholung in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Berlin 1960.

4 – Kuhl, w/o first name: Neubau des ersten FDGB-Urlauberheimes in Montagebauweise, in: Gesundheit und Lebensfreude für den Sieg des Sozialismus, Forum für die Mitarbeiter des Kur- u. Erholungswesens, 1967, issue 2, p. 6.

5 – The original project was a high-rise building developed by Wulf Brandstädter from the Halle Housing Construction Combine, which was first built in Halle in 1969, then in Dessau and Halle-Neustadt. Spiegel 2020, pp. 85 - 87.

6 – For details on the Schaabe project, cf.: Spiegel 2020, pp. 127 – 137.

7 – On the planning history of Oberhof, cf.: Spiegel, Daniela: Aus großer Geste wird Stückwerk. Die städtebaulichen Planungen für den Wintersportort Oberhof 1948–1989, in: Escherich, Mark / Nehring, Jens / Scheidhauer, Simon / Spiegel, Daniela: Utopie und Realität: Planungen zur sozialistischen Umgestaltung der Thüringer Städte Weimar, Erfurt, Suhl und Oberhof. Forschungen zum baukulturellen Erbe der DDR, Vol. 6, Weimar 2018, pp. 189 – 242.

8 – Spiegel, Daniela: Urlaubs(t)räume des Sozialismus, pp. 211 – 235.

Picture credits

1 (Cover photo) – Oberhof, Interhotel „Panorama“ (1967 – 69), Postcard 1970 (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, Kunstanstalt Straub & Fischer)

2 – FDGB-Holiday home „Fritz Heckert“, Gernrode, (1952 – 54), Postcard 1975 (Postcard archive Daniela Spiegel (Pka DS), VEB Bild und Heimat Reichenbach (VEB BHR), Photo: Doehring

3 – Tabarz, FDGB-Holiday home „Theo Neubauer“ (1951 – 53), Photo: FDGB, around 1962

4 – Ahlbeck, FDGB-Holiday home (ca. 1962 – 65), Postcard 1967 (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, VEB BHR), Photo: Darr

5 – Klink, Holiday home „Völkerfreundschaft“ (1960 – 62), Aerial photo: Deutsche Bauakademie, around 1969

6 – Saaldorf, Fin huts – Holiday home of Land- und Nahrungsgüterwirtschaft des Bezirks Gera (1970s), Postcard 1977 (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, VEB Foto König Lobenstein)

7 – Klink, FDGB-Holiday home „Herbert Warnke“ (1969 – 74), Postcard 1970s (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, VEB BHR), Photo: Kuka

8 – Model photo of the urban planning design for Oberhof, view from the northwest, Juli 1969 (Archive Bauamt Oberhof)

9 – see 1 (Cover photo)

10 – Oberhof, FDGB-Holiday home „Rennsteig“ (1972-73), Foto late 1970s (Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, Dia-Archiv der Professur Baugeschichte & Denkmalpflege)

11 – Oberhof, FDGB-Holiday home „Rennsteig“, Lobby, dining hall, bar, Postcard 1983 (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, VEB Bild und Heimat Reichenbach, Photo: Dick, Erlbach)

12 – Finsterbergen, FDGB-Holiday home „Wilhelm Pieck“ (1973-76), Postcard 1982 (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, Auslese-Bild-Verlag Bad Salzungen, Photo: Richter, Erfurt)

13 – Binz, FDGB-Holiday homes „Rugard“ and „Stubbenkammer“ (Photo: FDGB Das Neue Ferien- und Bäderbuch, Berlin, 1985)

14 – Schöneck, FDGB-Holiday home „Karl Marx“ (1978-85), Postcard 1980s (Postcard archive D. Spiegel)

15 – Frauenwald, NVA-Holiday home „Auf dem Sonnenberg“, Daytime café with room divider made of Lauscha glass beads (1970s), Photo in: Chronik EHG Frauenwald

16 – Suhl, VdgB / FDGB-Holiday home „Ringberghaus“, Farmer’s parlor, Postcard 1980s (Postcard archive D. Spiegel, VEB BHR), Photo: Voland

17 – Oberwiesenthal, FDGB-Holiday home “Am Fichtelberg” (1971-75), Knappenstube, Postcard 1976 (Postkartenarchiv D. Spiegel, VEB Bild und Heimat Reichenbach, Photo: Voland)

18 – Daniela Spiegel: Urlaubs(t)räume des Sozialismus. Zur Geschichte der Ferienarchitektur in der DDR, Wasmuth & Zohlen, Berlin 2020

0 Comments